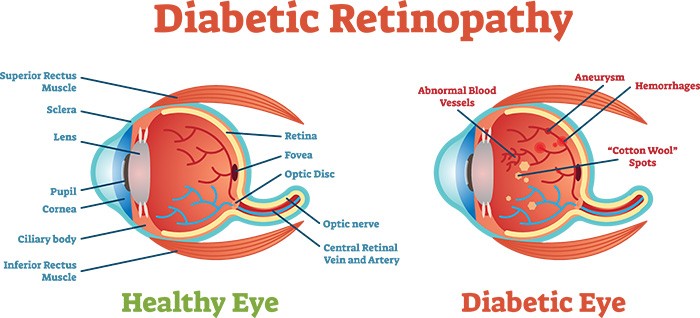

Diabetic retinopathy (die-uh-BET-ik ret-ih-NOP-uh-thee) is a diabetes complication that affects eyes. It's caused by damage to the blood vessels of the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye (retina).

At first, diabetic retinopathy may cause no symptoms or only mild vision problems. Eventually, it can cause blindness. The condition can develop in anyone who has type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The longer you have diabetes and the less controlled your blood sugar is, the more likely you are to develop this eye complication.

You might not have symptoms in the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. As the condition progresses, diabetic retinopathy symptoms may include:

Diabetic retinopathy usually affects both eyes. Diabetic retinopathy is a condition that occurs in people who have diabetes. It causes progressive damage to the retina, the light-sensitive lining at the back of the eye. Diabetic retinopathy is a serious sight-threatening complication of diabetes.

Diabetic retinopathy usually affects both eyes. Diabetic retinopathy is a condition that occurs in people who have diabetes. It causes progressive damage to the retina, the light-sensitive lining at the back of the eye. Diabetic retinopathy is a serious sight-threatening complication of diabetes.

Diabetes interferes with the body's ability to use and store sugar (glucose). The disease is characterized by too much sugar in the blood, which can cause damage throughout the body, including the eyes.

Over time, diabetes damages the blood vessels in the retina. Diabetic retinopathy occurs when these tiny blood vessels leak blood and other fluids. This causes the retinal tissue to swell, resulting in cloudy or blurred vision. The condition usually affects both eyes. The longer a person has diabetes, the more likely they will develop diabetic retinopathy. If left untreated, diabetic retinopathy can cause blindness.

Diabetic retinopathy results from the damage diabetes causes to the small blood vessels located in the retina. These damaged blood vessels can cause vision loss:

Diabetic retinopathy is classified into two types:

Other complications of PDR include detachment of the retina due to scar tissue formation and the development of glaucoma. Glaucoma is an eye disease in which there is progressive damage to the optic nerve. In PDR, new blood vessels grow into the area of the eye that drains fluid from the eye. This greatly raises the eye pressure, which damages the optic nerve. If left untreated, PDR can cause severe vision loss and even blindness.

Over time, too much sugar in your blood can lead to the blockage of the tiny blood vessels that nourish the retina, cutting off its blood supply. As a result, the eye attempts to grow new blood vessels. But these new blood vessels don't develop properly and can leak easily.

There are two types of diabetic retinopathy:

When you have NPDR, the walls of the blood vessels in your retina weaken. Tiny bulges (microaneurysms) protrude from the vessel walls of the smaller vessels, sometimes leaking fluid and blood into the retina. Larger retinal vessels can begin to dilate and become irregular in diameter, as well. NPDR can progress from mild to severe, as more blood vessels become blocked.

Nerve fibers in the retina may begin to swell. Sometimes the central part of the retina (macula) begins to swell (macular edema), a condition that requires treatment.

Diabetic retinopathy can progress to this more severe type, known as proliferative diabetic retinopathy. In this type, damaged blood vessels close off, causing the growth of new, abnormal blood vessels in the retina, and can leak into the clear, jelly-like substance that fills the center of your eye (vitreous).

Eventually, scar tissue stimulated by the growth of new blood vessels may cause the retina to detach from the back of your eye. If the new blood vessels interfere with the normal flow of fluid out of the eye, pressure may build up in the eyeball. This can damage the nerve that carries images from your eye to your brain (optic nerve), resulting in glaucoma.

Anyone who has diabetes can develop diabetic retinopathy. Risk of developing the eye condition can increase as a result of:

Diabetic retinopathy involves the abnormal growth of blood vessels in the retina. Complications can lead to serious vision problems:

The new blood vessels may bleed into the clear, jelly-like substance that fills the center of your eye. If the amount of bleeding is small, you might see only a few dark spots (floaters). In more-severe cases, blood can fill the vitreous cavity and completely block your vision.

Vitreous hemorrhage by itself usually doesn't cause permanent vision loss. The blood often clears from the eye within a few weeks or months. Unless your retina is damaged, your vision may return to its previous clarity.

The abnormal blood vessels associated with diabetic retinopathy stimulate the growth of scar tissue, which can pull the retina away from the back of the eye. This may cause spots floating in your vision, flashes of light or severe vision loss.

New blood vessels may grow in the front part of your eye and interfere with the normal flow of fluid out of the eye, causing pressure in the eye to build up (glaucoma). This pressure can damage the nerve that carries images from your eye to your brain (optic nerve).

Eventually, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma or both can lead to complete vision loss.

You can't always prevent diabetic retinopathy. However, regular eye exams, good control of your blood sugar and blood pressure, and early intervention for vision problems can help prevent severe vision loss.

If you have diabetes, reduce your risk of getting diabetic retinopathy by doing the following:

Make healthy eating and physical activity part of your daily routine. Try to get at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity, such as walking, each week. Take oral diabetes medications or insulin as directed.

You may need to check and record your blood sugar level several times a day — more-frequent measurements may be required if you're ill or under stress. Ask your doctor how often you need to test your blood sugar.

The glycosylated hemoglobin test, or hemoglobin A1C test, reflects your average blood sugar level for the two- to three-month period before the test. For most people, the A1C goal is to be under 7 percent.

Eating healthy foods, exercising regularly and losing excess weight can help. Sometimes medication is needed, too.

Smoking increases your risk of various diabetes complications, including diabetic retinopathy.

This is an injection into the vitreous, which is the jelly-like substance inside your eye. It is performed to place medicines inside the eye near the retina.Intravitreal injections are used to deliver drugs to the retina and other structures in the back of the eye, thus avoiding effects on the rest of the body. Common conditions treated with intravitreal injections include diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, retinal vascular diseases and ocular inflammation.

Procedure

Once your pupils are dilated, the actual procedure may take around 10 minutes and is carried out in minor operation theatre. You will be made to lie down in a comfortable position and anaesthetic (numbing) drops will be applied in your eye. Your eye will be cleaned with an iodine antiseptic solution. A speculum is inserted and the medicine injected into the vitreous. You may experience a mild discomfort during the procedure. Antibiotic ointment will be applied and the eye padded. Antibiotic eye drops need to be instilled for a week.

The doctor will see you the next day for inflammation or increase in intraocular pressure.

Instructions following an intravitreal injection

Normal effects following an intravitreal injection

Warning symptoms following an intravitreal injection

Although rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and cataract are potential complications of intravitreal injection, the most feared complication is endophthalmitis i.e. infection inside the eye (rates typically less than 1%).

You must contact the hospital immediately for advice if you develop these warning symptoms. It is very important to identify and treat this type of infection as quickly as possible.

Intravitreal injections for AMD, diabetic retinopathy (including macular edema) and retinal venous occlusion (RVO)

In AMD, diabetic retinopathy and retinal venous occlusion, there are increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the eye which gives rise to new vessels and macular edema. To counteract this, an anti VEGF injection is given. The anti VEGF injections are available as Lucentis, Macugen and Avastin (off label use).Anti VEGFs can rarely cause cerebrovascular events in the form of stroke or myocardial infarction (heart attack). Hence in patients who have a risk or history of ischemic heart disease or stroke, Macugen is preferred as it has less chance of causing such events.

These injections might have to be repeated more than once, depending upon the response of the eye.

Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide

Triamcinolone acetonide is a long acting steroid which is given in the eye in cases of macular edema secondary to diabetes, retinal venous occlusion or uveitis.You may feel black spots floating infront of eye, which is due to drug deposit in the vitreous. This will reduce over a period of few weeks as the drug is absorbed.

Triamcinolone may cause an increase in eye pressure or cataract.The intra ocular pressure can increase in 30% people who undergo the injection. The pressure in your eyes will be checked at every visit and eye drops prescribed if the pressure increases significantly. This increase is transient, and these drops can be discontinued after some time. Cataracts are not a serious problem for the first few months after the injection, but over 50% of treated eyes will eventually develop significant cataract if triamcinolone has to be repeated.

In AMD, diabetic retinopathy and retinal venous occlusion, there are increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the eye which gives rise to new vessels and macular edema. To counteract this, an anti VEGF injection is given. The anti VEGF injections are available as Lucentis, Macugen and Avastin (off label use).Anti VEGFs can rarely cause cerebrovascular events in the form of stroke or myocardial infarction (heart attack). Hence in patients who have a risk or history of ischemic heart disease or stroke, Macugen is preferred as it has less chance of causing such events.

These injections might have to be repeated more than once, depending upon the response of the eye.

Ozurdex intravitreal implant

This is an intravitreal steroid implant which is approved for the treatment of macular edema secodary to retinal venous occlusion. It has recently been approved by the US FDA for use in eyes with macular edema secondary to uveitis (ocular inflammation). This implant remains in the vitreous cavity for a longer duration compared to the intravitreal injections.